For one hilarious performance only.

Tony Vinicombe of West Sussex recalls a remarkable night at the theatre in the 1950s, which left him and his wife-to-be helpless with laughter.

IN HIS biography of Spike Milligan, Humphrey Carpenter mentions Spike’s tour of Moss Empires theatres with Harry Secombe and Max Geldray in June and July 1954.

He adds that there was “also a legendary week in which all three Goons appeared at the Coventry Hippodrome” and that it was “very far from a triumph“.

Since there is no other reference in the book to an all-Goons stage show, the reader is left with the impression that the Coventry week was the only occasion when Milligan, Secombe and Sellers appeared together onstage.

However, my wife and I both know this to be a false impression because we actually saw them on the stage of the Bristol Hippodrome some time in 1954 or 1955.

We were with a group of friends – I in my early twenties and my wife in her late teens. We were hovering on the brink of what is now called ‘a relationship’, so the occasion was significant for us.

The theatre was packed and we all sat patiently through the minor acts, awaiting the Big Three, expecting a Goon Show to be enacted. Therefore, we were a little disappointed when Sellers appeared alone. The disappointment was brief as Sellers reverted to his earlier career as an impressionist.

He did a series of brilliant impressions of current celebrities, but achieved a mighty roar of applause when he succeeded in becoming Winston Churchill without uttering a word. He simply adopted a firm stance, peered over a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles and placed a flat palm on each side of his thrust~forward stomach with elbows sticking out sideways.

Impersonations of Churchill were rife at that time, but Peter Sellers seemed to scorn his rivals with this mime.

He bowed his way off, and we all thought that now the three Goons would appear together, but the curtains parted to reveal a totally empty stage. When I say empty, I mean empty – totally devoid of scenery or standing props – all the way to the brick wall at the very back. This exposed space was enormous: it seemed almost as large as the auditorium itself.

There was just a microphone on a stand to one side near the footlights, but behind that the stage was in comparative darkness and, just as our eyes were growing accustomed to the low light, a door opened halfway up the brick wall, letting in the blue-seeming daylight of the narrow street behind the theatre.

In the background, we could see pedestrians passing by and could hear the sound of cars. A figure stepped inside. He plodded down a railed stone staircase running diagonally down the wall, and already there was laughter.

A stooped Spike Milligan wearing a large brimmed hat stepped on to the stage planks and started trudging towards us. But after only a few steps, he kicked something. It was a large roll of carpet, or perhaps canvas, which had not been apparent before.

It rolled ahead of him and he kicked it steadily forwards all the way to a few feet from the footlights, then abandoned it and at the same time threw his hat with perfect aim so that it landed on the microphone.

Instead of resting there, though, it went straight down to the floor: the hat had no top. This Chaplinesque surprise generated a gale of laughter and we were all transfixed.

He took the mike off the stand and started shaving himself with it. For about five or six minutes he said nothing – but kept up a series of relentlessly inventive and bizarre mimes.

By now the audience was in hysterics. Tears streaming down eyes, handkerchiefs dabbing – and Spike kept going. Eventually, he stopped and just stood looking at the audience. They kept on laughing, even though.. well, no.. because he was now doing absolutely nothing.

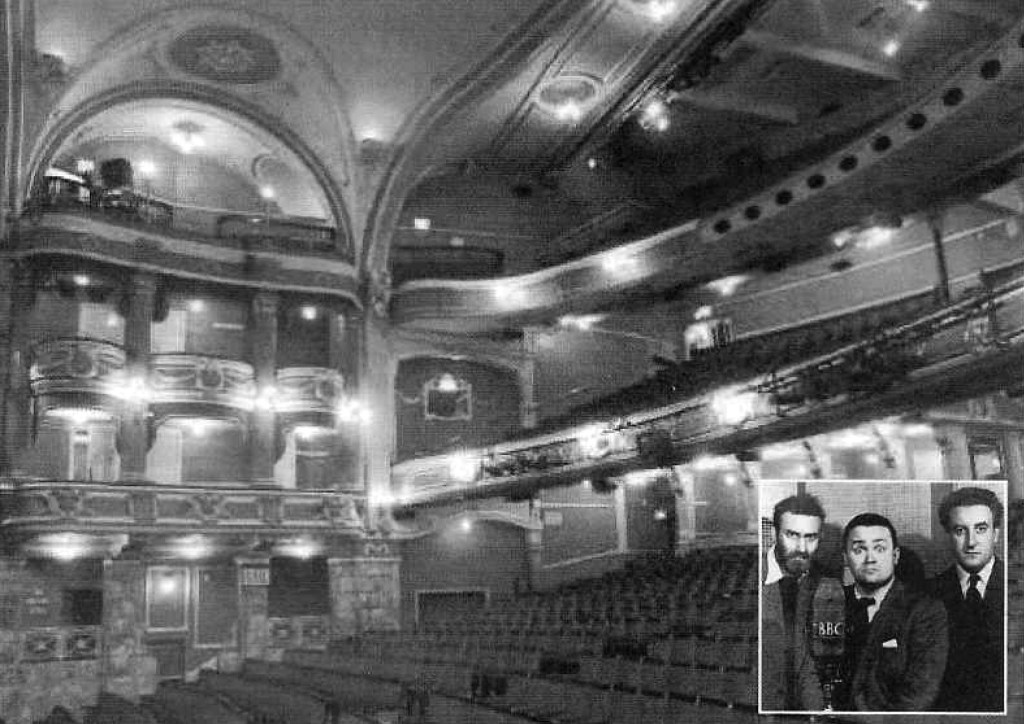

In all its splendour: the interior of the Bristol Hippodrome, where The Goons appeared.

I had been to variety shows at the Hippodrome several times to see the likes of Arthur Askey and Rob Wilton, but here was something entirely different. There was no reliance on telling jokes. This was anarchy and anything might happen.

Spike thrived on the tension this created, and flipped swiftly from one absurd idea to the next, sometimes adopting a voice similar to Eccles’s. Neither my wife nor I can recall further details of this performance except to confirm that when Milligan left the stage we were aching physically from laughing.

People talked about being “in stitches”. And for the first time I understood what this meant because I literally had “the stitch”.

Following Milligan, a coloured canvas dropped to conceal the back wall and halve the space. Then some men pushed a grand piano to the centre of the stage and, when they had departed, on came Secombe. These were early days in Secombe’s reputation as a singer.

If we had expected him to give a performance of the comic routines that had launched his career, we were to be frustrated. An accompanist sat at the piano and Secombe embarked on a recital of classic drawing-room songs. It was serious stuff and each piece was rewarded with modest applause.

Then, in the middle of (perhaps) the third song, a figure flitted past behind the piano from one side of the stage to the other. It happened so quickly we weren’t entirely sure whether it was part of the act or just a clumsy stagehand.

But then a bespectacled face appeared around the curtain and Sellers slunk out, ape-like, to take up a concealed position behind the piano. Secombe had been in the middle of a rousing refrain, but as Sellers and then Milligan crept about behind him, cavorting, struggling with each other, adopting ridiculous poses and generally sabotaging Secombe’s act, the laughter drowned out the singing.

Part of this sabotage included moving the piano from behind Secombe’s back whilst he was singing so that he fell when he reached out to lean on it. Eventually he abandoned his singing and joined in the mayhem. Whether it was scripted or improvised, it was impossible to tell. And neither my wife nor I can remember precisely how it all ended, except that there were grins and huge smiles all around as we slowly pressed through the exit passages into the street.

I suspect that we witnessed the only time an audience saw the brick rear wall of the Bristol Hippodrome’s stage, unless Beckett or Ionesco were there that night and became inspired.

But one thing is certain: Coventry was not the only city to enjoy the privilege of a live Goons performance not recorded for broadcast. And “very far from a triumph” is not a description of that Bristol Hippodrome experience.

This article first appeared in issue 121 of the GSPS newsletter, published in December 2007.