What was it like to attend a Goon Show recording in the 1950s? From the various memories and interviews which have appeared in GSPS newsletters over the years, we can piece together a bit of a picture.

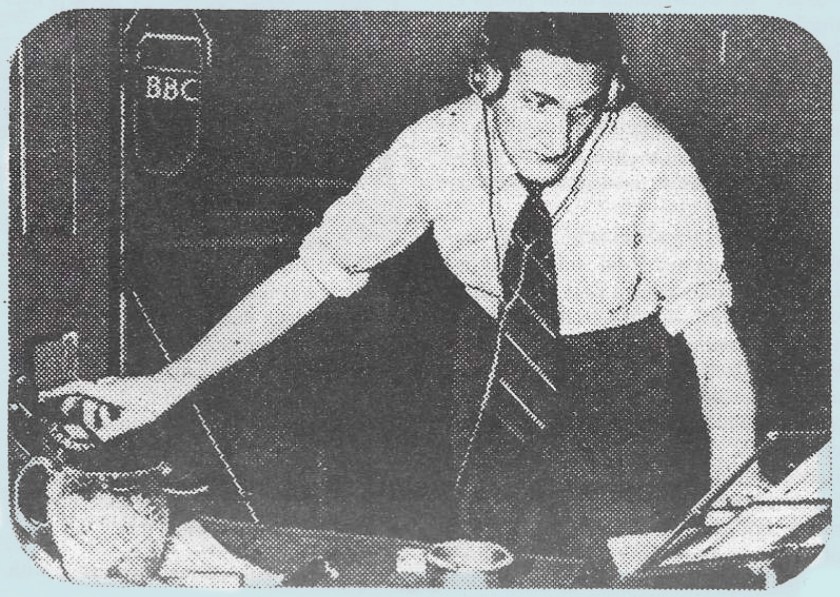

The first witness is Eddie Mills, a former BBC sound engineer who was interviewed in Australia in 1989. Eddie was a pioneer of using tape recording as it was developed during the 1950s, and of actually making the recordings in the Camden Theatre once the machines had become small enough to be portable. During the early series however, the audio recordings were made directly onto discs. Those disc cutting machines were in Broadcasting House, with the sound coming in on a wire directly from the theatre. Occasionally, Eddie managed to escape from his little room at the BBC HQ.

I’m speaking from not very much experience of the actual show because it was very popular and tickets were like hen’s teeth. Once the show became so popular there was no way in the world that you could get tickets without knowing somebody. The Beeb was as fair as they could possibly be in distributing these tickets, but there was such a demand. So, if I was off on a Sunday, I had to resort to taking a microphone, some tape or anything that looked official to the Camden Theatre, get through the doors and stand at the back and watch the show. It was very difficult to get in.

Tickets may have been hard to come by, but there were some fans who wrote regularly requesting tickets and managed to get to lots of shows. One regular, in his Member’s Memory published in a 1982 newsletter, described the queue outside.

The competition to be at the head of the queue was quite fierce. It was no good turning up much later than four hours before the doors were opened if you were hoping for a front seat. The very front rows were reserved for friends and celebrities, so the thing was to wait until the uniformed BBC minion wasn’t watching and then edge down a couple of rows, trying to look as if you were meant to be there.

Back in the queue, there was a busker who used to ‘work’ it. He played the squeezebox with a collecting bag clipped to the front of it. I think he came to recognise me, as he would sometimes pause, giving me an icy stare, implying I hadn’t put any money in the bag. I’d stare back as if I had.

My final memory is of my long blue serge overcoat buttoned right to the neck which gave me a semi official look. At the head of the queue and adjacent to the doors, I’d appoint myself doorman, and open and shut the doors to many minor minions who came and went during the waiting hours, efforts that would be followed by gales of boyish laughter. Ah me for the wild days of youth.

There would have been an afternoon of read-throughs and rehearsals before the stage was set and the audience was admitted. Eddie Mills recalled one of the shows he attended, watching how the atmosphere was built up, even before the real warm-up began.

There was a normal stage but with the curtains open, if there were curtains at all. On the front of the empty stage were three mikes. On the left hand side, as far as I can remember, was the band place, where you had about eight or ten seats with music stands in front of them and mikes sort of dotted around them. On the centre right there would be the grand piano for Ray Ellington, with drums and bass, I think, plus another mike for Max Geldray.

On the extreme right at the front of the stage was a little hutch arrangement, a three-cornered thing where the spot effects guy was crouching in front of his microphone. He had to do all these sort of weird doors, bells, whistles and things and, although he was partially hidden from the audience, you could, if you were on one side or the other, see what he was doing all the time.

The audience came in, sat down and started talking away, the usual sort of buzz of an audience waiting for things to happen. Suddenly a guy walked across the stage. He had a mike stand, or had a look at a mike stand, put it straight and walked off again with nobody taking much notice.

Right at the back there were two curtains, two little drapes, and one of them opened and there was Milligan putting his trousers on. That curtain then shut again and most people would miss it, obviously. But some of them would see it and then there would be a whisper going round saying “Hey, look at the back mmmmm…..” and this murmur would go up. Just for good measure, the curtain on the other side opened. It was always very incongruous because there were two of the very old column radiators behind, and I think it was Sellers putting his trousers on, with his hand on the radiator trying to keep warm.

Now the audience started getting interested and the murmur would drop it bit. This was still twenty minutes before it officially started, but something was happening. About two minutes later a music stand came flying in from the side of the stage and everybody would say “Oh!” and start murmuring again while some guy would wander in, pick up the stand and take it out again. Various things like that would happen, various things would crash in, building up the tension.

The pre-show warm up followed. It was performed by the cast with the announcer acting as master of ceremonies.

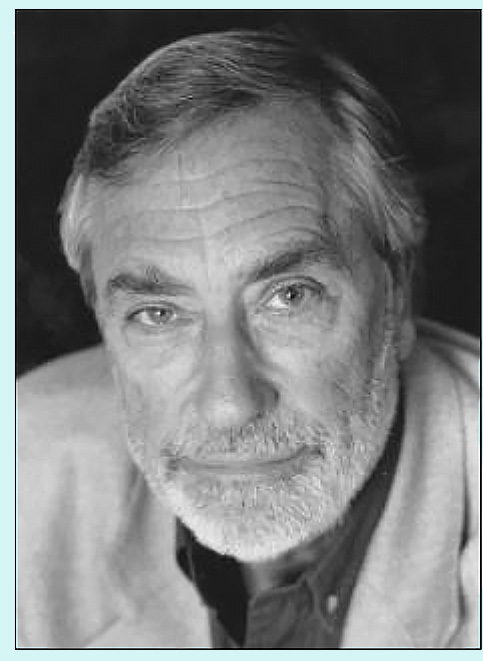

The Goon’s original announcer was Andrew Timothy. He left the show after three and a bit series, telling the press that he feared for his sanity. Goon Show humour really wasn’t his thing but, despite claiming to be appalled that a Goon Show Preservation Society actually existed, he attended meetings to talk about it on three occasions. In 1986 he explained to us why he really left.

While I was with them for two years, one of the things I had to do was to warm the audience up, and that’s a most unenviable task – to walk out onto the stage of the Aeolian hall, and there were ranks of people, sitting and wiggling their noses and their ears, and you’d have to sort of stir them up to some kind of life to start with, to get some kind of laughter!

So I had to do this job, and that was really the hardest job I had to do, by a long way. I noticed as time went past, that this damned show was becoming sort of … a sort of addiction, and I saw that gradually the rows in front of me, the fifth row and the sixth row and the seventh and the eighth, all contained exactly the same people, sitting in exactly the same seats as had attended the previous week, and the week before that. So you couldn’t sell the old tripish stories indefinitely. And I think that really was what got me out of the Goon Show, because I really couldn’t stand the thought of spending practically every Sunday of the year trying to jig up audiences.

The new announcer was Wallace Greenslade, who shared none of Andrew Timothy’s reservations. Wal’ took part in the Goon Show with gusto. From Member’s Memories again:

During the pre-show warm up, Wal would introduce any notables. I was there the night the Irish singer Cavan O’Connor stood up to take a bow, to be met with a withering hail of machine gun fire from the FX (spot effects) man, and riotous cheers from the assembled peasants. That was the spirit of the thing in those days.

Wal would always make his stock ‘funny’ by pointing up to the balcony and saying “Are you all right on the shelf up there? Good, because you can’t get out, the doors are locked”. There would he laughter from those who hadn’t heard it before, and knowing shrugs from us old hands.

Eddie Mills’ remembered the warm up too:

With about ten minutes to go, Wally Greenslade would walk in. He was quite tubby, always had a towel around his neck as he was wont to perspire a little. Some of the orchestra would wander in as well, sit down, find ‘A’, fiddle about with their instruments, that sort of thing.

So the interest would build, people getting a little more aware of what’s going on. Then Wally Greenslade would come up to the microphones and start, “Testing, testing. Everything all right there? Everything OK Bobby? Are we all right? Right. Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to this recording of The Goon Show. What we are going to do now is to do what we call a warm-up. We are going to see if we can do something to make you happy, laugh and that sort of thing. Tonight we have all the artists”, which he would then introduce.

The band came on, Wally Stott came on and the orchestra would be messing around for a little while, and then Max Geldray, followed by Ellington. So you’d get a stage moderately full of people. Whilst the introductions were going on Bobby Jaye, (on the mixing desk) would be getting his fader setting right for the applause, which was very polite at that time.

Then Wal Greenslade would introduce Sellers first. He used to come on and do a few things, a few funny voices, after which he would step back and Milligan would be introduced. Spike would do his funny voices and he used to tell a joke, he always had this wonderful joke. It was nearly always the same joke.

There was this guy walking in the forest one day when suddenly, in front of him, appeared a great big lion. The bloke took one look, it was just about to pounce on him, whipped out a violin and started playing. The lion just sat there transfixed, listening to the music. Suddenly there was a great hissing noise and this big snake appeared. He was just about to strike when the guy started playing again. The lion and the snake both sat there swaying to the music. Then this great trumpeting roar and this elephant would come in and was just about to trample him when he heard the music, and he’d sit down and listen.

This used to go on for some time with all these different animals and different voices. Suddenly this idiot baboon came into the clearing, saw this guy and ripped him apart, broke his violin and stamped it into the earth. The lion turned round to the baboon and said “What did you do that for?” and the baboon said “Eh?”!!

So that got the audience going. Secombe was introduced last and he used to do the limp-fall version of Falling in love with love. He used to hit that top C and just do a limp fall backwards. He just went ‘flump’ straight onto his back. Milligan was a good trumpet player and Sellers a good drummer, and they used to do a little jam session as well, so that by the time 5:30 came things were quite bopping and going quite well.

In those days, the previously mentioned spot effects man on the stage was John P Hamilton, who later went on to be a television executive. He became a great supporter of the GSPS and spoke to us several times. He recalled:

Around 7.30 p.m. we had a complete run-through for timing, then Peter Eton’s notes, and the audience would be ready for filtering in. It wasn’t unknown for us all to visit the Camden hostelry next door for a reviver before we faced the rigours of the warm-up.

That ten or so minutes was quite often my favourite part of the whole thing. Milligan and Sellers got up to all sorts of lunacy with the band joining in (with nuts like George Chisholm in the brass section it was to be expected). And Barry (Wilson, the grams operator) and I contributed when we felt it was appropriate. He usually had something in the disk rack that would get a laugh, and I wanted my opportunity to add something from my corner. One chance came when I had a couple of pistols loaded and standing by for the show. Harry always sang Falling in Love with Love with the band as his bit of the warm-up. At the end of the first line is the lyric “is falling for make believe” followed by three beats before the next line. I filled these three beats with pistol shots, all in tempo. Harry didn’t know I was going to do it, in fact, neither did I. It was a complete spur of the moment thing. Everybody collapsed – Harry, band, cast, audience. Thereafter, we kept it in each week until we got bored with it. But it certainly woke the audience up.

The film maker and artist Peter Watson-Wood attended many of the earliest Goon Show recordings in 1951 and 1952. He recounted his memories at our annual meeting in 2016. The memory of one particular warm-up had survived the intervening sixty plus years:

Every show had a warm-up. One of the team would come and get everybody in the mood and laughing. And I remember once it was Spike’s turn. And he came in and stood by the microphone and a very – I can’t remember his name – very respected and important public figure – much loved – had passed away that day. And Spike said something like, “I wasn’t going to mention this man. This is a warm-up, we’ve got to laugh. Come on!” And then he said in the prim voice of the producer, “I’m now going to give an impression of…” And he named this much revered, loved public figure and then lay down on the stage, flat, dead, lifeless. Well, the shock that went through the audience. “God’! Oh, that’s awful!’ And suddenly somebody broke and went “Pfffffft” and then the whole theatre was mad and rocking with laughter. He was a very respected and beloved man and it was therefore terribly insulting. But you broke the rules. This was not about keeping rules. It was about blowing the top off. It was a great send-off for the man, really.

And so, with the audience thoroughly warmed up, the recording would begin. More from Eddie Mills:

The scripts, I think from memory, were on a table near the spot effects, so they used to go and get their scripts which were stapled together. This made them difficult to read because they had to put the scripts behind the microphone and give a quick delivery. If they held the scripts in front of the microphone you wouldn’t hear anything.

The first thing they used to do was take the staples out of the script. Then if they were in a particularly ebullient mood, Wally Greenslade used to come up and say “Okay, recording room, we’ll go ahead in ten seconds from now”, and at that point you would hear a wail of laughter because all three of them used to get hold of their scripts and just throw them away. They used to go everywhere!! … In the next ten seconds they were all trying to find page one on the floor and of course everyone was laughing away like mad and so you never really got a clean start. You find that in most of The Goon Shows, there are gales of laughter going on before Wal says “This is the BBC Home Service”. Luckily there was nearly always an effect as we started which gave them just that little bit longer to find their scripts.

The visual gags which used to go on were frightening. Milligan in particular used to stand at the back of the stage, get his cue from Wally Greenslade and come to the microphone in an absolute rush, skid to a halt and say his line. Of course the audience fell about with laughter. They were always messing round at the back doing the usual sight gags, pulling trousers down, that sort of thing. This was one of the big complaints about The Goon Show when it first started, the fact that there were so many sight gags that it wasn’t good radio.

They’d pinch each other’s scripts, or you’d find three mikes up there and they’d all go for the one mike and they’d all be falling around. They’d take the bulb out of the cue light for instance, so you didn’t know when the cues were coming up. You remember that Ray Ellington took quite a few parts and had to get himself into place. They wouldn’t let him in half the time.

If we had a weird effect, Milligan would do a sight gag which meant that everyone would laugh. Everyone at home would think that the laugh was for the sound effect, whereas in fact most of the people in the Camden Theatre wouldn’t have heard the effect because of the noise that was going on.

They always used to go off for the band numbers and Max Geldray and Ellington, but didn’t always return on time. Wally Stott, who knew when the end of the musical piece was, would storm on the stage and there would be nobody there! So you’d start the second part and they’d come screaming in at a rate of knots hoping they’d get to the mike.

Little things like that would be sight gags that literally played a big, big part in the performance.

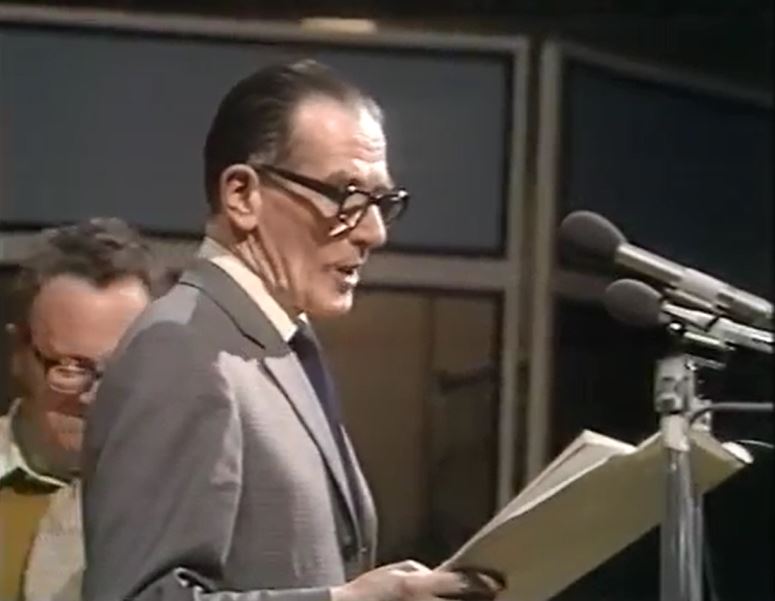

All this chaos would heap pressure onto the producer who had the job of making a radio programme out of it. That responsibility, from Series 3 to 6, belonged to Peter Eton. From Series 5 onwards, editing the shows became a little easier at least, as the recording medium moved from acetate disks to recording tape. Peter gave a long talk when he was our guest at the GSPS convention in 1976.

Spike, Larry Stephens and Erik Sykes were very good at writing ad-libs, but the programme had to be put out more or less as per script. Even in those days, for a radio programme, The Goon Show was very complicated to produce. It was a big job for John (Browell, later the show’s producer, then working the mixing desk) with spot effects, recorded effects, etc. I think he had 24 meters that he was using, hopping from one to another all the time. It was also a job for me, cueing correctly, so we didn’t have time for ad libs!! On some occasions Peter would be inspired to ad-lib and then Harry would muck about with his trousers, and this would lead to a whole sequence of ad-libs which occasionally I would leave in, but mostly had to cut out because they were filthy!

The show used to overrun like mad, and I always used to record the warm-up which was from five to twenty minutes. If the warm-up went well and the show wasn’t so good, it would go down like hell. So I was always hoping the warm-up would only be ‘medium’.

Occasionally they would get carried away doing some ad libs, so I’d let it run until the laughs went down and then they’d return to the script. If it had gone well they’d stay there and, as the audience were starting to file, out they’d start talking and the audience would sit down again, for more ad-libbing. I’d even record that with the band joining in.

Another of Peter Watson-Wood’s stories centred on an ad-lib. It may well have been from the days when Dennis Main Wilson was the producer, before Peter Eton.

They were by the microphone doing a scene together. Harry said, “Eat your words, you swine!” And so instead of answering, all of a sudden he stood up and started chewing on his script. And Secombe tried to do the next line, you know, everybody was pissing themselves. And then Spike leaned forward, grabbed a page out of his script and then Sellers came over and joined in the eating of the scripts and what was originally neat sniggers became uproar – absolute wonderful chaos. The audience were hysterical. And the real problem was every time they tried to bring calm to the theatre, they read another line, and then someone in the audience would go “Pfffft!” and we’d all start laughing again. And it was impossible for the artistes to read more script because all the audience and the actors were convulsed in hysterical out-of-this-world laughter. There was an atmosphere at these shows. And that atmosphere drove the shows in many ways.

But nothing lasts for ever. Our Member’s Memory correspondent lamented that things changed over the years:

But there, I’m afraid, the tale of joy rather fizzles out. The atmosphere at these shows became quite different. Gone was all the buffooning on the side. Gone forever was the pre-show warm up. The Goons came onto stage, read their lines with the minimum of enthusiasm and went away again.

Perhaps he’d just caught a quiet week or two. John Browell, who had been a stage manager during earlier years, was producer for the last two series.

At 7.30 we would do the show. They would have a rather large bottle of brandy and I would buy the milk. I noticed of course from time to time that the bottles of brandy were getting larger and larger, and I used to have to send my staff down there to drink copious quantities of brandy to try and keep the cast sober. I had a sober cast and a drunk staff.

He remembers plenty of antics during the warm-ups too

Harry was an extremely strong man, and he could lift both Spike and Peter up. This was the sort of thing we had during the warm up. Spike would go up to the curtain and hang on to it so that when the curtain went up his head would go up with it. Mike stands had wheels and they used to use them as scooters. Braces were a favourite. Peter would come along and do the old tine bit – ladies and gentleman etc., and whip away Harry’s braces, whereupon Peter’s trousers would fall down. I tried to get then to do it for the warm up far the fiftieth anniversary Goon Show. Peter cried off, because he remembered the terrible occasion once when they did it, and he hadn’t got any pants on.

We’ll finish on a memory received as recently as 2023. Trevor Harvey told us about having successfully obtained two tickets from the BBC for a recording of a Goon Show at the Camden Theatre.

It took place in January, 1960 and was entitled, The Last Smoking Seagoon. It was a memorable occasion for me. The Goon Show team appeared in great form, as did Geldray and Ellington. During the warm-up, Harry Secombe could be heard off-stage, singing loudly and slightly off-key, before appearing and continuing to do the same on-stage. Peter Sellers seated himself behind a drum kit and proceeded to play and finally Spike Milligan appeared, stage left, to loud applause. He just stood there, staring at the audience. Still staring, he walked very slowly across the performance area, before standing perfectly still again, still staring and then disappearing, stage right. Roars of laughter, thunderous applause and not a word spoken. I remember that the recording went well (except I was disappointed Spike had left Bluebottle out of the script). Then, as usual, Wallace Greenslade brought the show to a close, saying that this was ‘the last of them’. I thought he meant the last of the ‘Smoking Seagoons’ but, alas, that recording turned out to be the very final radio version of The Goon Show; apart from the 1972 Last Goon Show of All. To this day, I think how fortunate I was to have received those tickets!

Did you enjoy this page?

The original, much longer, articles these stories have been taken from, and lots and lots more, can be found in the book Goon Show News.

Click here for more info