The July 2014 issue of our newsletter came out shortly after Tony Gray had passed away. It was dedicated to the memory of the Alberts.

IT MAY BE RUBBISH

BUT IT’S BRITISH RUBBISH

During the Sixties, the Alberts (Tony and Douglas Gray) and Professor Bruce Lacey were Britain’s leading musical comedy trio, bursting out of the busy bowels of the Satire Boom and pioneering a style of stage eccentricities which influenced Monty Python, The Goodies and The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band.

Most of us have probably sampled the delights of YouTube’s episodes of A Show Called Fred, which also feature a couple of gormless looking musicians. That’s the Alberts! But a glance at their career history reveals that they were a lot less gormless than they looked, airing their talents in films, on records, in night clubs and in a phenomenally successful West End show. Their show was even scheduled to run first on the opening night of BBC2 in 1964, which was famously aborted in a farce of a different kind thanks to a power failure.

They became good friends with Spike, and appeared on You Gotta Go Oww! and many episodes of both Fred TV series.

webmasters note – Every time I have a conversation with our esteemed Chairman John Repsch, when he gets my name right and remembers that my surname is also Gray, I’m treated to a long discourse about the Alberts. John really is a fanboy, which comes across here….

John Repsch: The interview with Tony Gray took place via telephone to his farmhouse home near Carcasonne in 2012. More or less bedridden, Tony was thrilled that the outside world still remembered the troupe, and he was keen to offload memories of mayhem. Then, a year later, I was granted a face-to-face interview with Douglas.

The Tony Gray Interview

John Repsch: I was hoping to speak to the famous Tony Gray.

Tony Gray: Myself, yes. The word is infamous.

JR: It’s great to catch you.

TG: Well, I’m here most of the time because I’m getting a bit ill. I’m old – 86, I think.

JR: We’re all heading in the same direction. Anyway, I’m sure it hasn’t escaped your notice, but it’s going to be the 40th anniversary of The Last Goon Show of All.

TG: We weren’t in The Goon Show. We were only in A Show Called Fred and things like that on television, and of course we toured with Spike and Sellers, and we did our own show as well.

JR: An Evening of British Rubbish.

TG: That’s right. It got the best review any show has ever had in any theatre in the country.

JR: I went to an exhibition yesterday at Camden Arts Centre.

TG: Yes, by Bruce Lacey. Ours was a good partnership. It worked. Bruce was Michael Bentine’s prop-maker with all those fleas that jumped about.

JR: When he was with you, you were called The Massed Alberts.

TG: When there was a lot, but quite often it was just my brother Doug and me. We more or less split from Bruce when he gave a lecture, unscripted, in the middle of one of the shows… I actually met Sellers in a lift – it was an up-and-down relationship! [Laughs] I think we weren’t a threat to Spike or Sellers or anybody, really. We flitted about with Acker Bilk and all those people, and we did very well with the top brass because we never got drunk on duty.

JR: Have you seen yourself on YouTube?

TG: No, I don’t want to. I was very lucky. I had two divorces which were amicable, and I decided after all these years – my father was French – and I thought, I don’t want my children to see me disintegrate, which I’m beginning to do. I’m not too bad, but I can’t walk without a zimmer frame. I thought I’d go to the South of France, which I did. I’ve got two cars which I can just about drive, a dog and a cat and quite a large farmhouse. Three nurses a day come to see I’m all right. I’ve done a lot of things: drove a tank through Europe at the end of the war. There’s also a thing on the internet about the Alberts, because we opened BBC 2. I feel that phase of my life has gone. My children are about 50. I don’t mind dying.

JR: Well, we’ve not finished with you yet.

TG: My brother’s in Norfolk.

JR: I’d also like to get Dick Lester. He’s quite young. He’s only 80.

TG: I don’t like him. On A Show Called Fred he cut a lot of Spike’s stuff out. Later on television he said, “If I’d known then what Spike was, I wouldn’t have cut it, but we still get on.” Then we see Spike saying, “If I see him again I’ll f____ kill him!” The difference is that Spike became a friend. The children inter-mixed and I lent my house at Christmas. It wasn’t just a theatrical friendship, like it was with Sellers. With that business, we ad-libbed a lot, and Spike did too. I’m glad the Show Called Fred is still going.

JR: How did the Alberts come about?

TG: My father’s name was Albert. He died when I was 7, so we moved to England with my mother. Our signature tune was Dolly Grey.

The Alberts came into being when my brother played the sousaphone with Humphrey Lyttelton at the Albert Hall, and I saw potential, and I played unusual instruments so no one could say I was rotten. The tricornet: it was the only one that ever existed. Louis Armstrong had one but I don’t remember it ever being played. It’s a miniature trombone, and that played harmony to my brother’s trumpet playing. You’ve got the record, I suppose?

JR: I haven’t but I know someone who has. How did you get on with Spike and Sellers?

TG: I got on very well with Spike. He was a very wise man. He once said to me, “The difference between you and me, Tony, is I’m mad and do mad things, and you’re mad and eccentric and you do mad things and think there’s a logical reason for it.” Brilliant. We met the Queen. We did a Royal Command Performance. Have you heard of Brewer’s Rogues, Villains and Eccentrics because there’s a lot about us in that? I didn’t like a lot of the people in show business. I see Max Bygraves has died. I didn’t like him. Arthur Askey – awful. Tommy Trinder – my God! And actually Max Miller bought us a dinner…

I had an old GPO van. And I even got the red and white striped tent, so I’d put it outside. Therefore parking was no problem. The wardens thought that was a GPO van. I lived at Windsor then. One day there was a bloke hitch-hiking – I always picked them up – and he said, “Oh, that’s strange. I’ve just seen a show with a bloke like you in it.” I said, “Really?” He went on to describe it but I wouldn’t tell him it was me. That’s my personality. Another thing I started with my brother, we started the Old Lorry Club with Lord Montagu which is still going. He was a great friend. We used to borrow his 1920 fire engine to go to Brighton. I always get out of things, like The Temperance Seven. Douglas started it and gave them the name.

JR: I thought they were very good: Pasadena.

TG: I didn’t like the discipline. I wouldn’t tour. I had children and a bloody great rectory… I gave away all my instruments and I’ve come here to die, but as long as I can go on I’ll live. But I want it nice – not in Norfolk in the pissing rain.

JR: What do you remember about Spike? Did you get to talk to him personally?

TG: I was with him for months. We did a show with him in Wales. We were the orchestra! [Laughs]

JR: Was it a play you were doing?

TG: No, sort of variety. Long before Python we were doing things like The Exploding Tenor at the Albert Hall. You know that scene where the man blows up from eating too much? We did that ten years before in the Albert Hall. You know Mario Lanza died of overeating, so I sang, “I’m only a strolling…” And [mimics explosion] – a little bomb in my black bag with fluck. Do you like the idea of fluck?

JR: Fluck?

TG: It’s bits of tripe and stuff.

JR: And you had padding on to make yourself fat?

TG: Yes, of course. And a black moustache, like that commercial for Go Compare. We did New York. We opened a theatre in San Francisco. Did you know we went into opera?

JR: Did you?

TG: Yes, we joined the Royal Opera House as singers and dancers, and we went all over the world: Korea, Japan, Palermo, La Scala Milan. Can you imagine performing there when you haven’t got any talent?

JR: You must have had a good voice.

TG: The voice we weren’t wanted for. There were 200 in the chorus but we had to do different things.

JR: If you were on the stage in these sketches and blowing up, that sounds like Spike material.

TG: Yes, we were all together. He liked explosions as well.

JR: You say you weren’t competing, but that sounds the kind of stuff he would do.

TG: We did similar things many times, but there was never any rivalry. We used to go to dinner together. He’s been to my house; I’ve been to his many times. And it wasn’t to do with theatre necessarily. He was a funny bloke sometimes, and he was odd. I think the pressure on him was too much and, of course, he had the Army experience which was similar to mine, where I was driving through Germany at the end of the war and it was terrifying – dead people. He was actually thrown out for cowardice but then someone put him in ENSA. The story is that he was behind a dead cow and, of course, if you put your head up, there was a sniper waiting for you, and every now and again this cow farted.

Secombe I didn’t like much. I felt he was rather hollow; it was all front. But with Spike it was sincere. And Sellers had no self-confidence at all. On the record, we had this little chap called Joey, who plays the clarinet. He wasn’t very well but we got him into one of the shows – it might have been a Fred. And he drove into the car park – it might have been Lime Grove or Television Centre. Well, he smashes into a car, but no one sees anything. It was a big car. At the end of the day Sellers came up and says, “That little chap has smashed my car up, but we won’t say anything.” You see, when you get a book about Sellers or Spike, they run them down. When you’re dead they can attack you. But Spike was a marvellous man.

One day a friend of mine – a Nigerian girl – said she’d like to see Spike. So we went along to the theatre, because we followed them in with British Rubbish. But then he refused to see the Duke of Kent – he never sees anyone without a chin! So I said, “I don’t know what mood he’s in.” We went backstage in the interval. We chatted, and then he brought us both on and he introduced us and said, “What do you think of this beautiful girl?” These are stories that I’d like broadcast.

JR: Of course.

TG: I’ve got his biography describing him as awkward. He didn’t suffer fools. I’ve been with him in a restaurant and somebody comes up [imitates Eccles]. Well, you don’t want that, do you?

JR: Spike was such a mixture of people.

TG: Absolutely. But I think he was forced into it. Like me, I wouldn’t have dreamt I was going to do compering at the Albert Hall – I was born just round the corner. And the fact that you’re standing there at La Scala, Milan on your own, on the stage with my brother – incredible. Because I had no real talent, not in terms of Pavarotti or someone. Of course, we met all those, had dinner with Nureyev who was a bit awkward. It was a good life. Have you got my address?

JR: No, Tony.

TG: You’d better have it: Albert Hall, Orsans, France.

JR: That’s short. You’re obviously well known.

TG: I call it Albert Hall because it’s satire. We used to work a lot with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore and Frankie Howerd.

JR: Do you have any memories of the sketches you did on A Show Called Fred? There’s one where Spike is dressed in a nightshirt and he’s ushering you and Douglas into this room, and you are having difficulty carrying these huge sousaphones, and eventually you all fall over on the couch. And that’s for the world to see on YouTube.

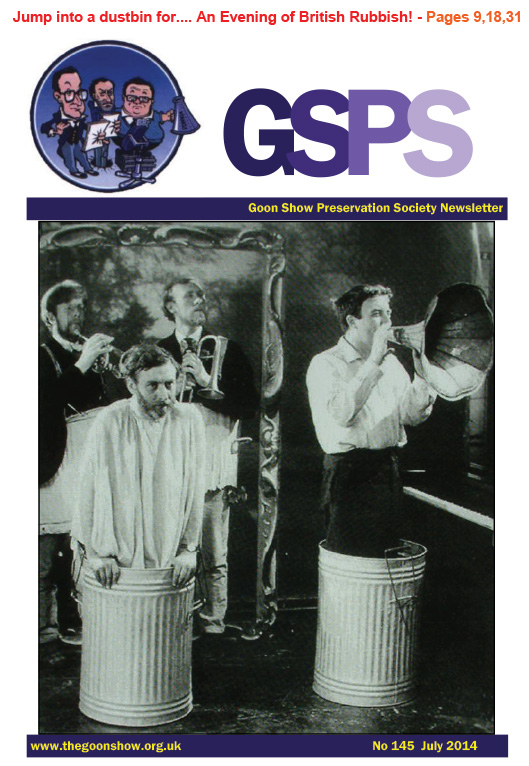

TG: What about The Dustbins Dance? We did two versions of that. [Sings] “When you’ve got no trousers on and no underpants, jump into a dustbin and dance.”

JR: Who wrote that – Spike?

TG: Yes, and we did our own version.

JR: Did you appear in any episodes of The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d?

TG: No, we did A Show Called Fred and Son of Fred.

JR: There was another gentleman who wrote some of that stuff: John Antrobus.

TG: Yes, he’s still around. He was very young. The Bedsitting Room was marvellous. There’s an atomic explosion, the prime minister turns into a parrot and Lord Grytpype-Thynne turns into a bed-sitting room and lets himself out for half-a-crown a week.

JR: It was directed by Dick Lester.

TG: He didn’t ‘get’ us, if you understand me. We did The Three Musketeers at the Royal Court. He later did a film and copied great lumps from it. I was quite friendly with Oliver Reed and went to his house and so on. A very nice man. He took my daughter out on a lake in one of the films we were in. I played his brother.

JR: Roy Kinnear fell off his horse.

TG: The stuntman couldn’t do it, and Lester insisted that someone had to do it, so it was Roy. But Roy wasn’t a ‘tidy’ man, he wasn’t athletic. They took him to a Spanish hospital but it was too late. When they shot the film, they had enough left over to do a sequel. Oliver Reed was furious because they weren’t told they were in a sequel.

JR: Do you remember Valentine Dyall?

TG: Oh God, yes. He was splendid. And when we did The Three Musketeers, we wanted him for Cardinal Richelieu. Perfect. But I feel very ashamed of this. The director, Lyndsay Anderson, came in with a short, bulky, American, ginger man and said, “I want him to be Cardinal Richelieu.” Dick Haymes. What I did at the beginning of the play: I had a huge photograph frame, covered it with paper, and he bursts through it for his entrance. And we had an organ that came up through the floor playing Bach… Valentine was always broke: “I say, could you lend me half-a-crown. I want to go to the BBC canteen.” I gave him a car and we got on very well. His father, Franklin Dyall, did similar things, dramatic plays like The Hair. (Someone finds a hair in an envelope.) Valentine had a sense of humour. In France, before the curtains open, you have this noise: [Imitates banging]. That means: “Shut up, the curtains are going to open.” So we made that noise, the curtains opened and there was Valentine mending his boots.

JR: You were on a record called You Gotta Go Oww!. How did you get involved in it?

TG: I didn’t like it much. We knew George Martin very well. We used to go round there in the afternoon for biscuits and tea, and I took his secretary to a show. A very nice man, well-mannered, and I told him he shouldn’t have been in show business; he should have been a conductor.

JR: You went round to his house for biscuits?

TG: Yes. My brother said they were stale. Also, Gilbert Harding. We went to tea with him…. One funny thing was a penny-farthing we had. I rode it onto the stage, and Bruce, with his electronic business, wired it up to an amplifier and played a tune on the spokes. [Imitates guitar twanging “Tell me the way to go home, I’m tired and I want to go to sleep”.] And somebody gave us a full-sized stuffed camel, and the legs were all rocky, so we brought it onto the stage. And I had cut the side out and painted the ribs white and put an African wooden xylophone in. And Bruce came on like Lawrence of Arabia and played ‘The Sheikh of Araby’ on it. And at the end, the tail was like a cranking handle: you’d turn the handle and two coconuts fell into the bucket. I do think that no one was compared with us. That was the joy.

JR: It seems that you were in at the beginning with these eccentric acts. Were you around before Spike, because he was in a comedy jazz band called The Bill Hall Trio?

TG: That was really before us. In a way, he was more conventional than us. It wasn’t until he got into his stride with The Goon Show. That’s how I met him. I wrote to him, showed him my card. Douglas didn’t fit in the photograph on it, and Spike was so alert. He could see that I’d cut the legs off a chair to make it the right height. He thought that was terribly funny. So we met and I walked out of there with a contract. We laughed so much. That was the thing about him: we laughed a lot. He said, “Are you married?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “You can have affairs. I’m not married. I can’t.”

JR: You appearing in the Fred shows, did that help your career?

TG: I don’t know. I didn’t care about my career. We would do cabaret at nightclubs. I never thought about it really. There was a bloke called Hymie Zahl – imagine who – an agent! He wanted us, so we went into a restaurant to meet him, and he said, “Could you boys hone your props a bit?” He had no idea. He ended up throwing himself off that big tower in Tottenham Court Road: Centre Point.

JR: Did you know Michael Bentine?

TG: I quite liked him. Bruce was also Bentine’s propmaker with all those fleas that jumped about. The trouble with Bentine was: he was too good. Spike said, “There’s got to be a sword fight here – who can do sword fighting?” And Bentine said, “I can, I’m an expert.” So what they did was get a real expert sword fighter in an old raincoat and, of course, Bentine won.

JR: Do you remember Graham Stark?

TG: I blew him up once. I had a sort of ticker-tape machine that exploded. No one should touch it, really. He blew it up and burnt all his front clothes. But he was laughing. He was a great friend of Peter Sellers. There’s a word: coterie. I never really knew him or went to his house. But if I met him in Soho or somewhere, we’d chat about f____ all.

The Douglas Gray Interview

At the time of this chinwag, Douglas was in Kelling Hospital, Norfolk, convalescing after an appendix operation. Although very hard of hearing, due to a career full of exploding camels and other ear-splitting blitzes, he provided a tantalizing taste of what he had been up to over the years.

John Repsch: How did the Alberts come into being?

Douglas Gray: First of all playing in jazz bands. It was a good jazz band: Steve Lane’s Southern Stompers. After a bit my brother and I used to do a double-act in nightclubs: just a cornet, trombone, melochord, concertina. Then we heard of Spike and Eric Sykes. Spike, when he was demobbed, did lots of performing at the Woolwich Empire and places like that. Then Eric and Spike were doing scriptwriting above a greengrocer’s in Shepherd’s Bush and we heard that Spike was putting on a television show with Peter Sellers, so Tony wrote to him. Of course, Spike rejected that. Then he said, “Come along and meet Peter Sellers.” So we went and did A Show Called Fred and Son of Fred on ITV. It was The Goon Show live on television. Although Tony and I were never in The Goon Show, we went along and did a warm-up one day playing brass.

JR: Your act was very surreal.

DG: I don’t know – a nightclub act. We got on well with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. We did an act with Bruce Lacey at Peter Cook’s Establishment Club in Soho. That’s where we met Lenny Bruce. He did an act, and the whole thing was in telling the audience what we did! He was up to his neck in drugs, but a lovely man. He got onto a friend in New York, and we got booked up for a New York nightclub, The Blue Angel. Bruce, Tony and I went out there on the Queen Mary and we did shows on board ship every night. They gave us treats: clocks with ‘Queen Mary’ on. And we performed at The Blue Angel, which was well received. I think we had to leave New York because all the guns in Cuba were pointed on America, so we went home.

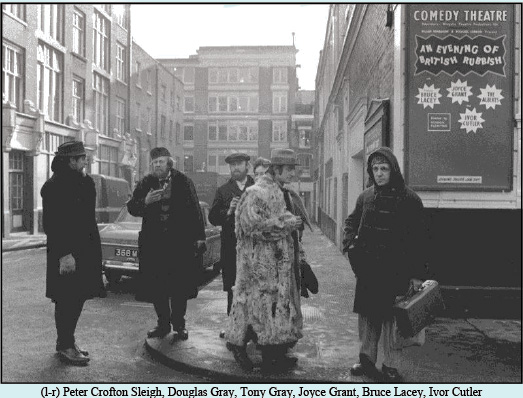

Then we did a few more acts. In the meantime my brother and I were working with wholesale newsagents, W. H. Smith’s, and used to deliver papers to The Dorchester and Harrods every morning about 5. We’d pick our vans up, go to the nightclub, leave the vans outside, do our act, then do the papers. Then we put on a show in the West End, called An Evening of British Rubbish. Bruce Lacey used to make all the props. He had a full-sized, stuffed camel from a taxidermist. He used to wheel it on the stage and we’d play The Sheik Of Araby. He’d pull off a big panel from the camel’s rib-cage, and there was a xylophone in it which he’d play. We had orchestral bells and used to play Tchaikovsky’s 1812. Ivor Cutler was with us: a Scottish Jew of Russian extraction. A marvellous person.

JR: Do you remember any sketches from A Show Called Fred?

DG: We had a funny bloke called Richard Lester who everybody hated. Spike liked him. We did it every fortnight. I think I saw a couple of them, though I didn’t have a television set. Not many people did have.

JR: You had to rehearse first with a script?

DG: Oh, yes. I used to bring my greyhound. I’d be working all night for W.H. Smith’s, then in the morning I’d get up at 9 o’clock, drive to the studio in Wembley and do these shows.

JR: Was there much improvisation?

DG: I don’t think we were allowed to do improvisation. Spike was very strict: he’d tell us what to do and we did it. We had a convention of opticians, and we all had little eye baths, and we made a toast to opticians, and instead of drinking it, we poured it in our eyes. Kenneth Connor was a lovely man. Tony and I met him when he was getting very old. We were doing an ‘Allo, ‘Allo!, and we had a long chat. I do enjoy doing television: a day out and a good meal. We also did You Rang, M’Lord? and Lovejoy.

JR: Do you remember Valentine Dyall?

DG: Tony and I put on The Three Musketeers, and Valentine played the Duke de Richelieu – the villain – and he was marvellous. It was a very cold winter and he didn’t have an overcoat, so I gave him one of mine. It was a fantastic Blueberry, but it was made for the old taxi drivers, a very long thing. Do you remember The Man in Black? [Imitates the deep Dyall voice] “I’ve got a story for you about a man who looked in the mirror and he didn’t see his face.”

JR: When you had the scripts, were they finished?

DG: No, sometimes things would change. One day we were ready to go on, and they found in the wardrobe a complete set of Nazi Gestapo uniforms. So they changed the whole script and all came out in Nazi uniforms!

JR: How did you get on with Spike?

DG: He was up and down. He had a bad time in the war and got blown up. I wouldn’t call it shellshock but he was fighting authorities all the time.

JR: Was he fighting the television company as well?

DG: All the time. He ended up in an office near Hyde Park, but he got a bit funny with some of his secretaries about changing the toilet rolls. He helped to rebuild a lovely old tree called The Goblin Oak. It was all little animals and birds, and he spent a lot of time doing it up.

JR: Did you get to know him socially?

DG: Yes. He gave me a trumpet to get done up because he nearly smashed it to pieces in a rage. He was always playing it.

JR: I heard that he adored the Alberts.

DG: We never actually copied what he did, but we were on the same wavelength. We did a show with him on Welsh television in Cardiff. Telly Welly they called it. It was him and a man called Bob Todd. And I brought my greyhound in. He made us all dress up as Druids. He even made a little druid costume for the dog. [Recites in dramatic Welsh accent] “You can see the light coming over the western mountain. It’s getting brighter and brighter and brighter. Now where’s that half-crown I dropped here last week?”

JR: What about Peter Sellers?

DG: A funny man. He was a lovely bloke – very clever. He was in the RAF during the war. His mother was Jewish and his father Roman Catholic. He was in a play up the West End, Brouhaha, and Tony and I saw it. We gave him a present. It was a real Edison Bell phonograph, all lovely brass and mahogany, and he really loved it. We did a Royal Command Performance at the London Palladium – that was Peter, Spike, my brother and I. It was when Prince Charles was at school in Australia, so we all had to dress up as kangaroos. Halfway through the show I saw this man in a fur coat in the wings – Bud Flanagan – and he said to me, “Shall I go on?”. I said, “Yeah, go on, go on.” And he went on and brought the house down.

JR: ‘You Gotta Go Oww!’

DG: I remember it well.

JR: You were the Massed Alberts.

DG: The Massed Alberts could mean three or eight. It varies: whatever is going on. They were my brother and myself, I think my elder brother – he’s 93 now and lives in New Zealand; and Joey Clark the clarinet player: him and me were founders of The Temperance Seven.

JR: Is he still alive?

DG: No, he’s been dead 50 years. And there was also Gravely Stephens, of course, for that record.

JR: He was a Massed Albert? How did you get involved in that record?

DG: Spike invited us for several funny things. There was big trouble with the Chinese Embassy. They were keeping the British Ambassador locked up in Peking, so Spike decided he’d have a march and post a letter in the Chinese Embassy complaining, but he couldn’t get anyone else to take part. There was one man – a big, tall chap who used to take part in some of the shows – and Spike asked him. He said, “What? No, I’m an actor. I’ve got to consider my position.” So Spike ended up with about four people and myself. I had to go to Boosey & Hawkes to borrow a drum for my brother, and we marched to the embassy from Baker Street. Spike put the letter through the letterbox. And there were about a hundred policemen guarding us.

JR: Do you recall anything else about You Gotta Go Oww!?

DG: I know we did another one with Peter Sellers – My September Love – and they had a set of orchestral bells which kept falling over.

JR: George Martin recorded an LP with the Alberts.

DG: Yes, Goodbye Dolly Grey and old war-time songs like Blaze Away. When we did our West End show, George insisted that we did it in his Abbey Road studio one Sunday, and we had an audience and the props. Along the roof’s rafters there was about 50 years of black dirt. When we had an explosion, the black dirt blew up and Ivor Cutler ran for his life. We were in George’s office one day and the phone rang and he said, “What? What are they called? Beatles? Tell them to get a good haircut and I’ll talk to them later.”

JR: Do you remember Graham Stark?

DG: He was a nice bloke. I had a lovely tickertape machine – clockwork. Instead of writing, it used to come in morse. And my brother wired it up for an explosion. This was a rehearsal. And Graham Stark went up to it and said, “I wonder what these wires do,” and stuck two wires together, and there was such an explosion. [Laughs] Graham used to work quite hard and he’d have rows with Spike.

JR: You also made a record called The Morse Code Melody.

DG: There were two. [Sings] “Oh, oh that Morse Code Melody…” And the other side was Sleepy Valley. Bruce Lacey did it. [Sings] “Everybody loves the fireside, Picture sitting by a fireside, In a cosy little home, You can call your very own. Let’s go down to Sleepy Valley. All of my troubles, Cares of the day, Like silver bubbles blowing away.” We accompanied on the brass.

JR: Do you still see Bruce?

DG: No. He is in Wymondham in Norfolk. I haven’t seen him for a long, long time.

JR: Do you remember anything about The Morse Code Melody?

DG: Yes, my brother doesn’t believe me but it was taken from a jazz tune. [Sings] “Oh, oh those ragtime melodies.” It was off a cylinder. Nobody would mind because cylinders are finished. All mine were stolen when I lived in the vicarage with my wife and two kids. They were 5 and 7 when she left. I had to bring them up. I had a housekeeper and she was stealing everything. The C.I.D. said, “Either get rid of your antiques or get rid of your house.”

JR: I’ve been told that you went on TV to perform it, and you were asked to mime instead. And you refused and sang another song while that one played.

DG: I don’t remember. We did a show at the Metropolitan Theatre. My brother was playing a phonofiddle and had it all wired up, and the theatre manager kept lowering the microphone, so I was down on the floor playing. And my brother pressed one of their magic buttons, and a sheet of flame flew out of this thing and landed on the double-bass player in the pit and set fire to his trousers. We had to give him about 8 quid for a new pair of trousers. We did a show with Max Miller. He used to tell all these filthy jokes in rehearsal, but when the show came on he told clean ones. He used to wear trousers with plus fours and flowers all over them. Oh, show business.

JR: Would Spike have liked to perform in your British Rubbish?

DG: No, he never wanted to perform. He told us a few things, though. He came to see it and was a great help.

JR: What did he suggest?

DG: The quiz show. My brother was the quizmaster and I was in the audience. He blindfolded me, then said, “Questions: What’s the first letter of the alphabet? Too late,” then hit me over the head with a rubber club. Then: “Think of a number.” I’d say, “Five.” He’d say, “Wrong,” and hit me over the head. In the end there was a saxophone wired up to explode. “Now, what instrument am I playing?” and he presses a button and there’s a shattering explosion. “An exploding saxophone.” – “Right. Now ‘Sense of touch’: What is this?” (I’m still blindfolded.) And he pours a bucket of water over my head. I’m standing there dripping wet. And I say, “Can I have that question again, please?” and I get another bucket over my head. And he says, “You’ve won the lucky prize.” The lucky prize was in the shape and size of the old try-your-strength machines, which they used to have in circuses. But instead of the weight going up, he had a long pole inside a big canister which was absolutely crammed full with old rubbish, like cigarette ends, dust and orange peel. He’d say, “Right, try your strength,” and I’d pick up this huge mallet. Inside the box of rubbish was a sweep’s brush and I’d hit it: wallop, up it goes and all this muck used to fly over everybody. Then Bruce Lacey would come on dressed in a guard’s uniform and say, “Ladysmith’s been relieved,” and they’d play Goodbye Dolly Grey. We marched off, but at the back of the stage was an old Austin 7, and on the chassis were all the props, and that would drive off.

JR: Is that your favourite memory: the time you spent on An Evening of British Rubbish?

DG: Oh, yes. We never went to parties. We used to drive home to our wives. I was living on the barge then. My first week’s wages had been very poor, but now we were getting a great, heavy envelope with £120. But we still bought the same rubbish we used to buy, like Government surplus raincoats. We didn’t really change.

We are indebted to Tony’s son and daughter, Albion and Sheba Gray, Douglas’s daughter Pandora and to Douglas’s carer Tim Snelling for presenting us with a wealth of photos and newscuttings. Someone should write a book about those guys.

The Alberts feature on the compilation CD By Jingo It’s British Rubbish, along with The Temperence Seven and The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band.

It’s available on Amazon